Sometimes we measure cylindrical(ish) structures on a bedside ultrasound. On some occasions, the patient later gets a radiology performed scan and our measurements don’t match. This could be why.

Cylinder Tangent Effect

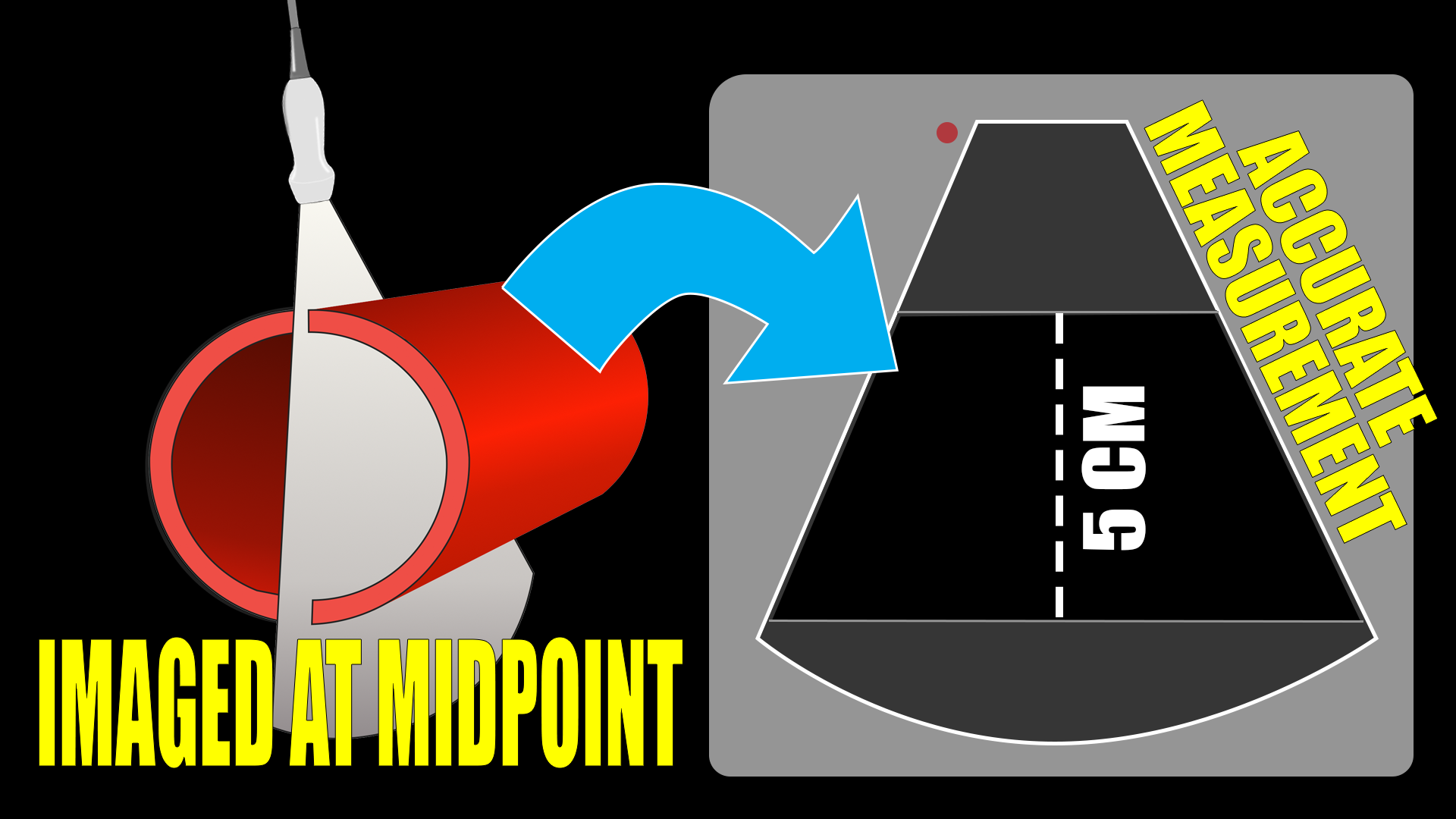

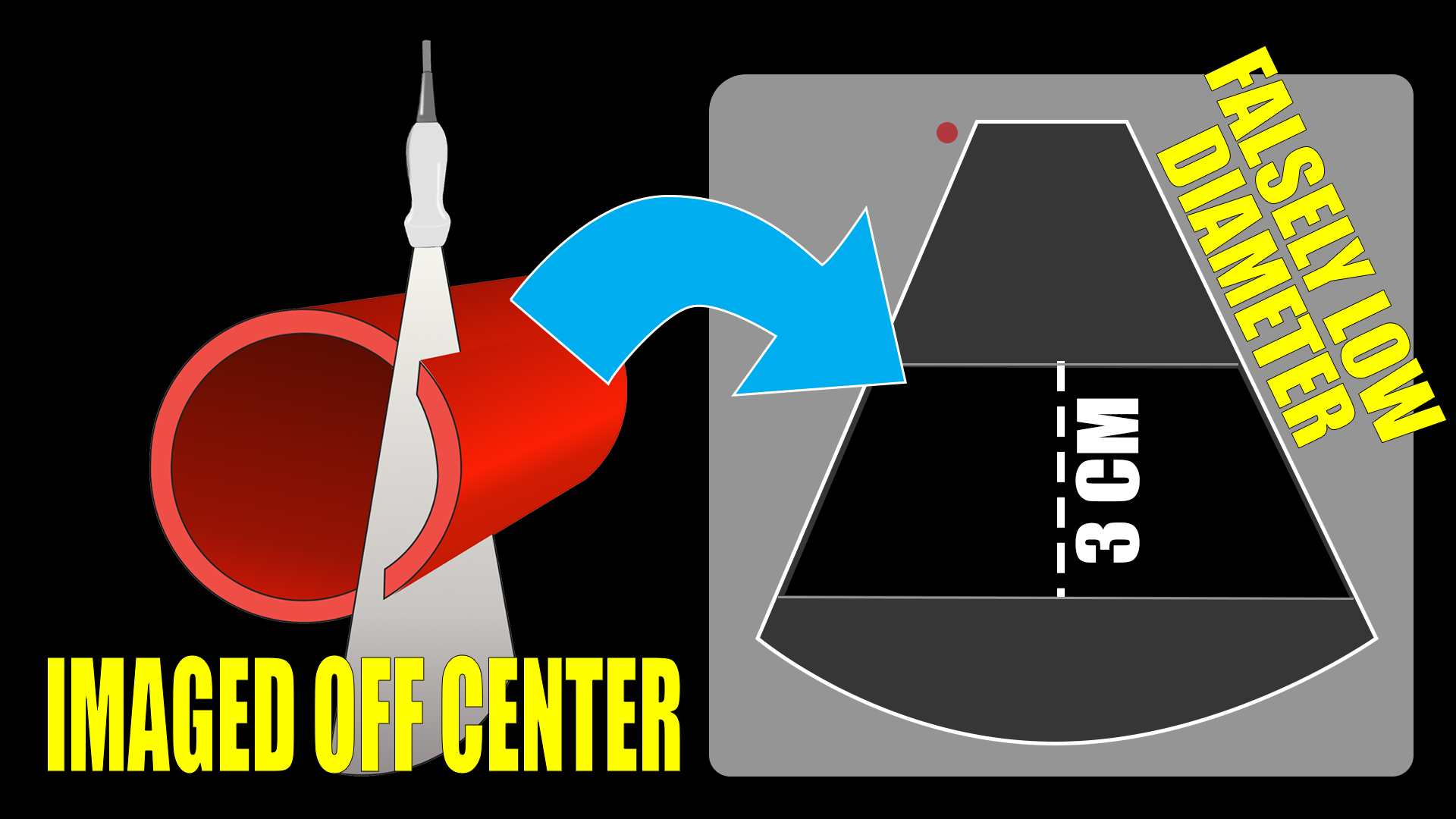

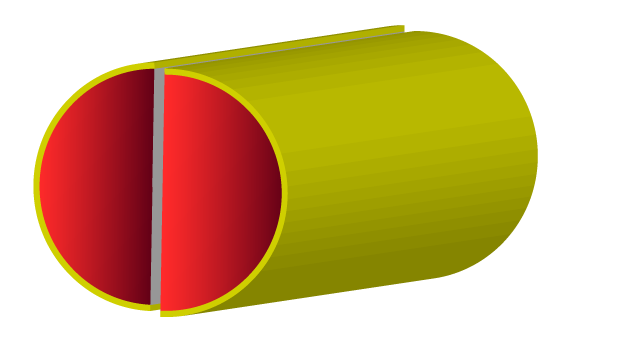

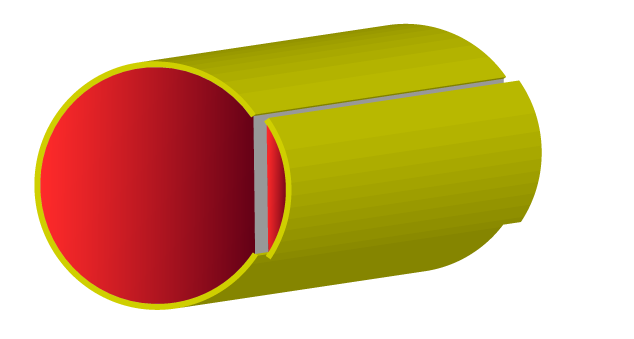

The “cylinder tangent effect” or “cylinder tangent error” happens when we view a cylindrical (tubular) structure in long axis with the beam not passing through its widest point. The ultrasound catches an off-center slice, which can make the the structure appear smaller on the screen than it actually is.

It is simple to see in the images below how measurements would be affected if the still image that was used to make the measurements was off center.

Clearly, anything other than the true diameter will give a falsely low representation of the size of structure being measured.

When would this be a problem?

We do not make a lot of decisions from quantitative measurements on point-of-care ultrasound. But this would come up when measuring aortas, common bile ducts, gall bladders, loops of bowel, appendices, etc. It’s a good thing to be aware of.

This phenomenon is why we generally prefer measurements of tubular structures in short axis. On the other hand, this would only under-measure. In other words, if you see an aorta in long axis that measures six cm – it’s pathologic. It could be larger than that, but it is safe to say that it is at least six cm.

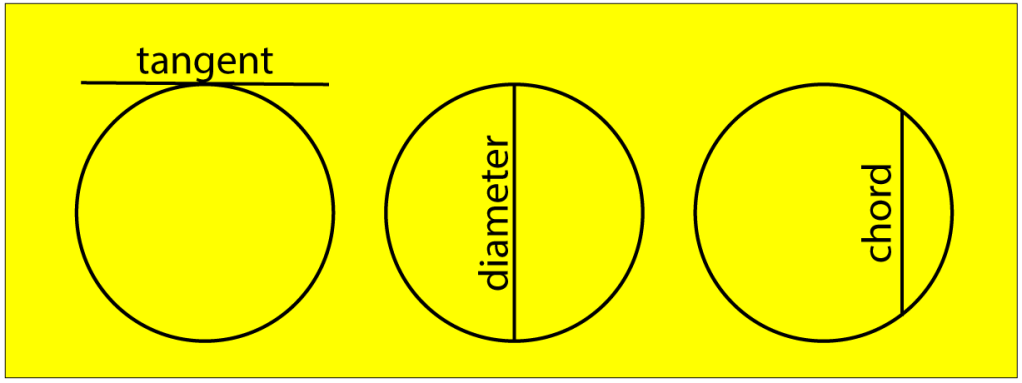

Is this poorly named?

I think so. I can’t find the origin story for why this error is called the “cylinder tangent effect,” but it is not based on a “tangent” to a cylinder/circle. It looks to me like it is actually an artifact based on a chord, rather than a tangent. Shouldn’t it be called the cylinder chord effect? Perhaps I’m missing something.

So, I can’t mess this up in short axis?

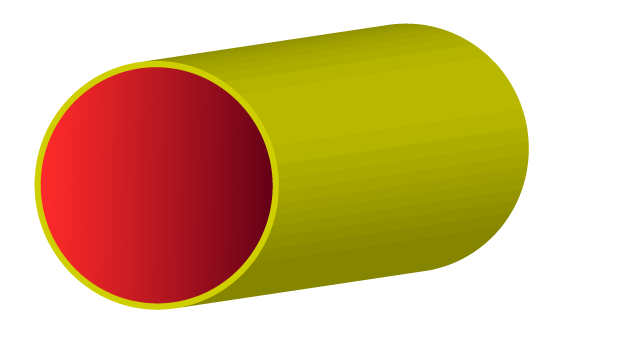

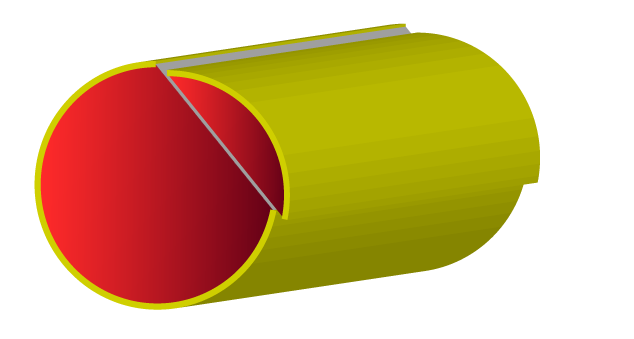

You won’t get this exact error in short axis, but there is a similar phenomenon you could encounter on short axis imaging through cylindrical structures. I’m not aware of a name for this phenomenon, but It probably has one. You would see this error if the long axis of the cylinder did not run parallel to the surface of the body that you were scanning through. The result would be an oblique slice through the structure in question, which would give a falsely high measurement.

In the example below, we see how the angle between the long axis of the cylinder being measured and the ultrasound beam can cause a discrepancy in the size of the image displayed on the screen. As you can see, the true diameter is the same in both cases, but the measured (apparent) diameter is drastically different.

The animation is a rather extreme example – especially for an aorta – but the concept is clear. Most things you would measure run “close enough” to parallel to the body surface that this probably is not commonly a cause of significant error. Like the cylinder tangent effect, however, it is something to be aware of.

What about non-cylindrical structures?

The same concept would apply to any round(ish) structures: ovaries, gall bladders, testicles, hearts, and cardiac chambers, for example. You could easily under measure if you didn’t have a still image that was a cross section though the true diameter of the structure.

Final thoughts

If you’ve measured something on your ultrasound and send the patient for a radiology performed study, chances are their measurements won’t match yours exactly. Measuring errors aside, this may be why. The tech probably considered (subconsciously) these errors and took the time to get the best cross section of the structure before making the measurement. If you watch them do a study, they often freeze their image and then use the sine loop to scroll back until they find the single best image. They use that carefully selected one, rather than the wherever they happened to be when the image was frozen.

Keep this in mind when measuring cylindrical structures, particularly if you are in a situation where a small error could effect your plan. For example, if your patient has signs and symptoms concerning for a ruptured AAA, the details of the size of the aneurysm don’t matter. On the other hand, if you have a patient with biliary colic, an 8 mm common bile duct might alert you to the presence of a stone within the duct, whereas a 5 or 6 mm diameter would not. Clearly the treatment of biliary colic/cholelithiasis is very different from that of choledocolithiasis.

Scan happy, my friends.