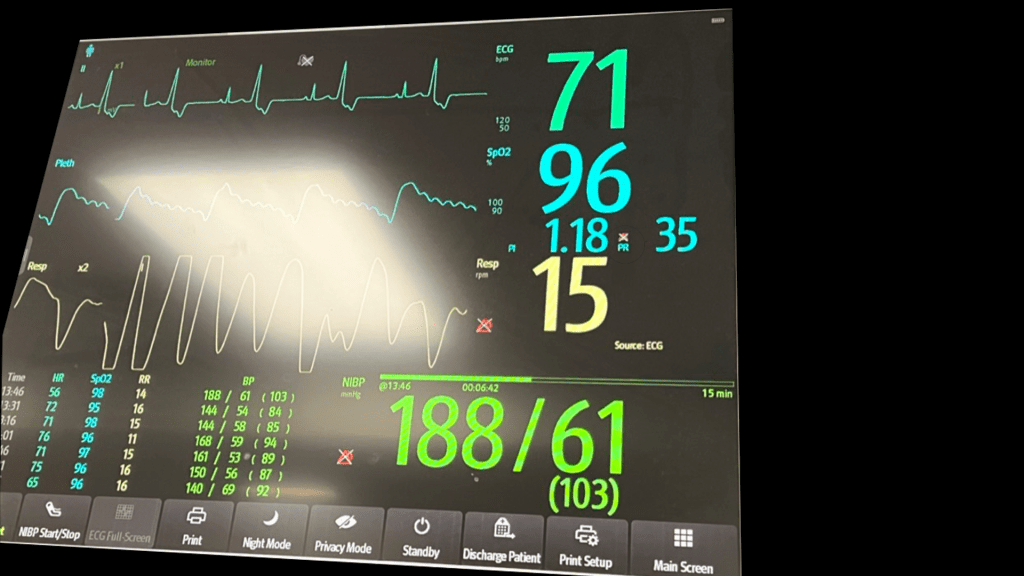

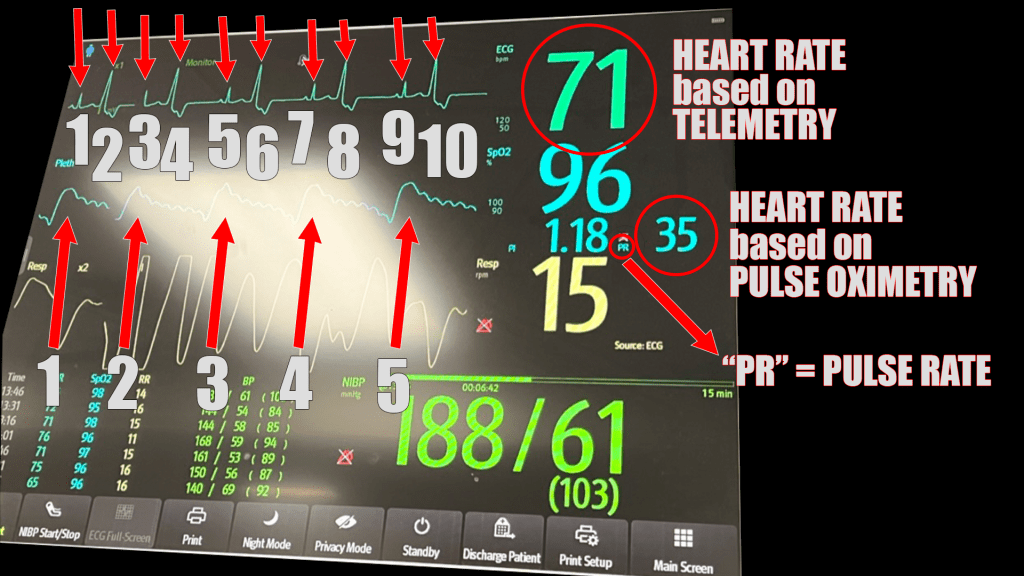

Here we see a nice example of ventricular bigeminy. Besides the rhythm, do you notice anything strange on the cardiac monitor?

This was 60 something year old fellow who had a syncopal spell while he was fishing with his grand kids. He went in and out of this pattern of ventricular bigeminy frequently while he was on the monitor in the ED. (Please excuse the glare from the overhead light; this is a photo of a monitor.)

Do you see the teaching point?

Notice what the monitor reports as the heart rate: 71 beats per minute.

You may not spend much time thinking about it, but this monitor actually reports the heart rate in two ways. The rate is 71 as noted above based on the telemetry reading. However, the pulse oximeter reading (whose graphic representation is termed the “photoplethysmograph” or “pleth” for short) also reports a heart rate. In this case it reports 35 beats per minute.

Why aren’t they the same?

At the end of the day, the cardiac monitor is measuring electrical activity. It has an algorithm that is uses to calculate a “heart rate” based on how many QRS complexes it detects. In this case, there are 10 complexes on this brief rhythm strip on the display.

The pulse oximeter, on the other hand, detects instances of pulsatile flow. It is detecting what you would feel with your fingers if you were to check a pulse in the radial artery, for example. The display shows that on the “pleth” we see see there are five beats detected – exactly half of the 10 QRS complexes detected on telemetry.

What that means, in this case, is that the electrical activity we call a “premature ventricular contraction” (PVC) is not actually causing a contraction – at least not enough of one to send an adequate amount blood around the vascular system to be detected by the pulse oximeter as pulsatile flow.

So, which one is correct?

When I touched the patient, the heart rate I could feel was 35. I’d say that was the correct number.

I think it would be too simple to say that no PVC results in ventricular squeezing that causes a palpable pulse. I suspect most (or at least some) do. It may be that even in this case, the PVC was causing a very weak contraction that just didn’t move enough blood to be felt in the extremities (neither by the pulse oximeter nor my fingers on the radial artery). I suppose that we could have answered the question definitively if we had put the ultrasound on his heart and looked for movement of the left ventricle or aortic valve. That would confirm or deny whether or not blood was moving at all. I didn’t think of that at the time.

Other than the fact that you should understand how the equipment you are using works, I can think of a few applications where recognizing the difference between electrical activity and a mechanically detectable pulse might be helpful. For example, if you were pacing someone (trans-thoracic or trans-venous) you might notice the photoplethysmograph changing when you have achieved mechanical capture as opposed to electrical capture. (Although I don’t think I would throw out the tried and true method of having an assistant with a finger on the patient’s pulse just yet.) Also, when T waves are particularly prominent, we can see the same phenomenon. The telemetry will sometimes count the T waves as “beats” and will give a number twice the actual heart rate. The photoplethysmograph tells the tale, however.

Interesting point! I’ll stick to “pleth” instead of photoplethsymography.

LikeLike

Pingback: What’s the heart rate: follow up | Searcy EM