Regardless of your opinion on its necessity, the first step in putting end-tidal CO2 to use is understanding what it is. Here are the basics.

Pulse oximetry is simple: high is good, low is bad. Capnometry, on the other hand, is a little more complex. Sometimes low numbers mean one thing, other times they mean something else. Sometimes rising numbers are a very good thing, other times they are an ominous finding. Let’s clarify a little of this.

Potential ED uses of quantitative end-tidal CO2

- Assessing the quality of CPR

- Monitoring for ROSC

- Early detection of ETT displacement

- Trending PCO2 levels

- Early detection of apnea during procedural sedation

Some generalities about capnometry

- Carbon dioxide levels in exhaled air can be used as a noninvasive and continuous way to estimate the PCO2. (It’s not perfect, but it is close enough in most circumstances)

- It is a good thing if the number is getting closer to 40 and a bad thing if the number is getting further away from 40 – in either direction.

- Carbon dioxide comes from oxidative phosphorylation, which requires oxygen. If oxygen is not getting to the tissue (i.e. during cardiac arrest) the carbon dioxide level in expired air will be very low.

- Because it is not being produced

- The ETCO2 will also be low in a respiratory alkylosis or compensated metabolic acidosis.

- Because it is being exhaled at high rate

- Clinically, it should be obvious whether the patient is tachypneic or apneic/pulseless, but both could cause the ETCO2 to be low for very different reasons.

- Because it is being exhaled at high rate

- If the ETCO2 is very low (~ less than 10) during CPR, your CPR is not having the desired effect of getting oxygen to the tissues.

- You should probably move your hands, push harder or faster or slower, change compressors or make some other adjustment to how you are doing the CPR.

- If the ETCO2 is “low” (less than 40) but not “very low” (less than 10) during CPR, you are doing good CPR.

- Enough oxygen is reaching the tissues to sustain at least some cellular respiration as evidenced by the production of (and exhalation of) at least some carbon dioxide

- If your ETCO2 jumps abruptly during CPR (say from 12 to 25, for example), the heart has probably started beating and is doing a better job of oxygen delivery than your CPR was.

- If you are doing a procedural sedation and the patient is hypoventilating or apneic, the ETCO2 will rise before the oxygen level will fall.

- If you see that, you should get ready to provide BVM ventilation, or use reversal medications/ airway repositioning, etc., regardless of the pulse ox

- If after intubating a patient the ETCO2 flat-lines, the tube is probably in the esophagus.

- This would likely happen before the pulse ox fell, especially in a preoxygenated patient

Confusing points

The line goes up and down, but it only reports one number

The number displayed on the monitor is the value at the end of exhalation – the “end-tidal CO2” or “ETCO2“. That’s when the concentration of CO2 in the air flowing past the sensor is most likely to represent the concentration of CO2 in the alveolus, which should be roughly equal to the PCO2 in the blood when a diffusion equilibrium is in place. So, the number displayed next to the capnometry waveform, the ETCO2, is a surrogate of a surrogate of something you actually want to know: the PCO2.

The PCO2 itself is a surrogate as well. During a procedural sedation, it is a surrogate marker of hypoventialation and apnea. During CPR, it is a surrogate for cellular metabolism / tissue perfusion.

[The same phenomenon occurs in pulse oximetry. We don’t really care how much oxygen is bound to hemoglobin, we actually are interested in whether or not the tissues have enough oxygen for metabolism. Pulse ox is a noninvasive and continuous way to monitor something that (at least mostly) correlates with the parameter we actually want to know.]

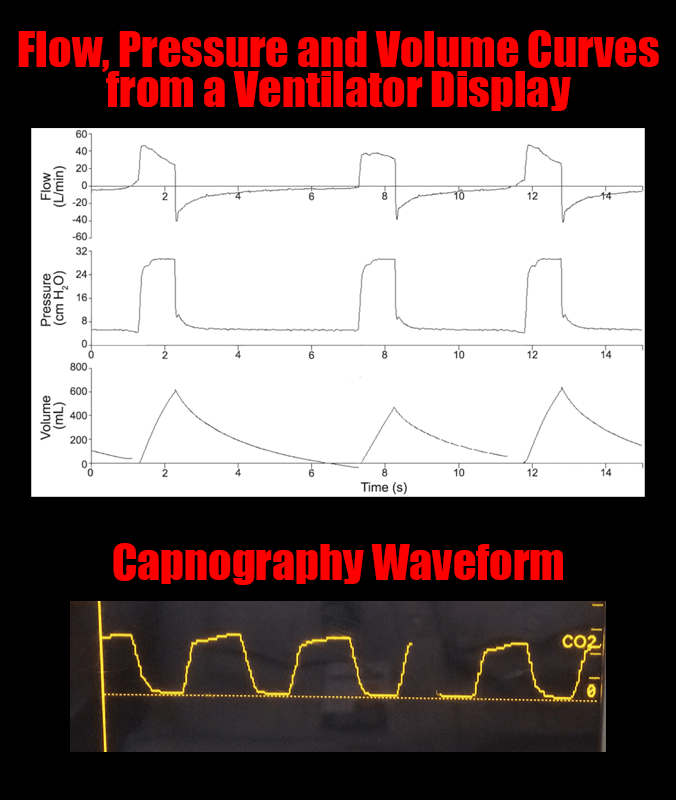

The capnograph looks like the display on the ventilator, but it’s different

The graphic representation of the capnometer’s measurement is what you see on the monitor. It does look similar to the flow, pressure, and volume curves on a ventilator display.

The confusing point is the fact that on the ventilator display, the curves go up during inhalation and back to baseline during exhalation. The opposite is true on the capnography waveform: CO2 goes up during exhalation and back to zero during inhalation.

Where is the measurement taken?

This will seem trivial to people who use this modality commonly, but I see learners frequently who have not put thought into this part of it yet.

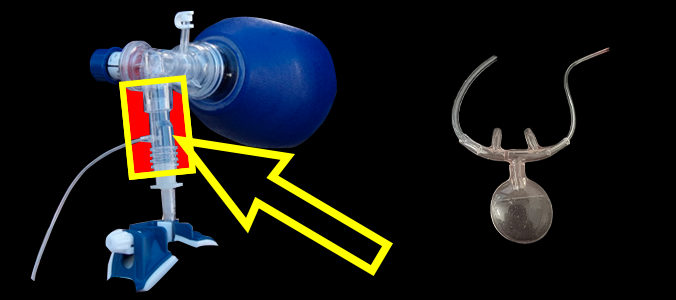

There are two scenarios, and the equipment varies a little among vendors. The first scenario is the intubated patient. In this case, the sensor makes the measurement from a device that (at our shop) has to be attached between and endotracheal tube and ventilator tubing. In a non-intubated patient, on the other hand, the sensor is in a device that looks similar to a nasal cannula, which measures the CO2 concentration of air just outside the nose/mouth. (There are others, but that’s what we see in our department.)

If hypoventilation makes the pCO2 go up, why would it be low in cardiac arrest?

This is very confusing. I think of it like this*: if the patient is hypoventilating but their heart is beating and bringing oxygen to the tissues (that is to say that oxidative phosphorylation is still generating CO2) the CO2 will rise because it is not being exhaled as fast as it is being made. If, on the other hand, the blood has not been moving and oxygen is / has not been getting to the tissue, oxidative phosphorylation is not happening, and CO2 is low because it is not being produced. It is a very ominous sign If you are doing CPR and the ETCO2 is never getting above 10 even with optimizing your technique.

There is more subtlety to it than what was presented here. One thing in particular is the idea of PCO2-ETCO2 gradient. The gradient gets large in some disease processes making the absolute number of the ETCO2 a less reliable estimation of the PCO2 (although trends may still be of value). The ETCO2 can be affected by other things as well – giving sodium bicarbonate during CPR, for example.

Let’s wrap it up

If you are familiar with it and deploy it in the proper settings, ETCO2 can serve as a noninvasive, real time way to monitor a surrogate of a surrogate of a surrogate of perfusion during CPR or as a canary-in-the-coal-mine for procedural sedation. Also, since there is no “reserve” for exhaled CO2 it changes earlier than the pulse ox. This can make it useful in real time for things like confirming ETT position.

Hopefully that’s enough to get you started. There are plenty of places to find more information if you are interested. Put some thought into it and decide if it would be helpful on your next shift.

Links for a deeper dive

*Someone else may have a better or deeper understanding of this phenomenon. This is my understanding. Again, its confusing.