I’ve done this topic before, but I left some meat on that bone. Let’s get into the weeds.

A point of care DVT study takes less than 10 minutes. It would take considerably longer to call in a technologist and wait for a radiology read. However, the savings in time and throughput are only worth it if our test is as good as theirs. Sensitivities of POC scans have been reported to be as high as 93-100% in appropriately trained/experienced hands – but that is a huge caveat: “appropriately trained and experienced hands.”

Achieving that level of mastery has some requirements.

- We have to know the anatomy backwards and forwards.

- We have understand what the imaging requirements are and meet those criteria on every case.

- We need the self awareness to realize when we have and have not met all of those requirements.

That’s what training is for – residency in our case. With that understanding, there are several common mistakes that I see learners make over and over. Those mistakes – some are very subtle – can be enough to lower your sensitivity to a point where the time saved is no longer worth the risk of not ordering a comprehensive, technologist-performed-radiologist-interpreted study. Let’s look at those.

What are the requirements for the study?

Protocols for the point of care version of a DVT ultrasound call for compression images at two critical points. These points are where blood flow is most turbid, which means they are where clots most frequently form. The two points are:

- Where the common femoral and saphenous veins merge in the inguinal area of the proximal thigh – the “saphenofemoral junction”

- The popliteal vein just above its trifurcation behind the knee

Other protocols (three point compression protocols) add a third “point”: the [superficial*] femoral vein in the thigh. I teach a version of the three point study. I prefer to think of ~5 cm “zones” around the first two points. That gives a look at those spots as well as slightly above and slightly below them. I also agree with compressing several points down the [superficial*] femoral vein between the groin and where it enters the adductor canal. I don’t routinely use any spectral Doppler tracings nor augmentation.

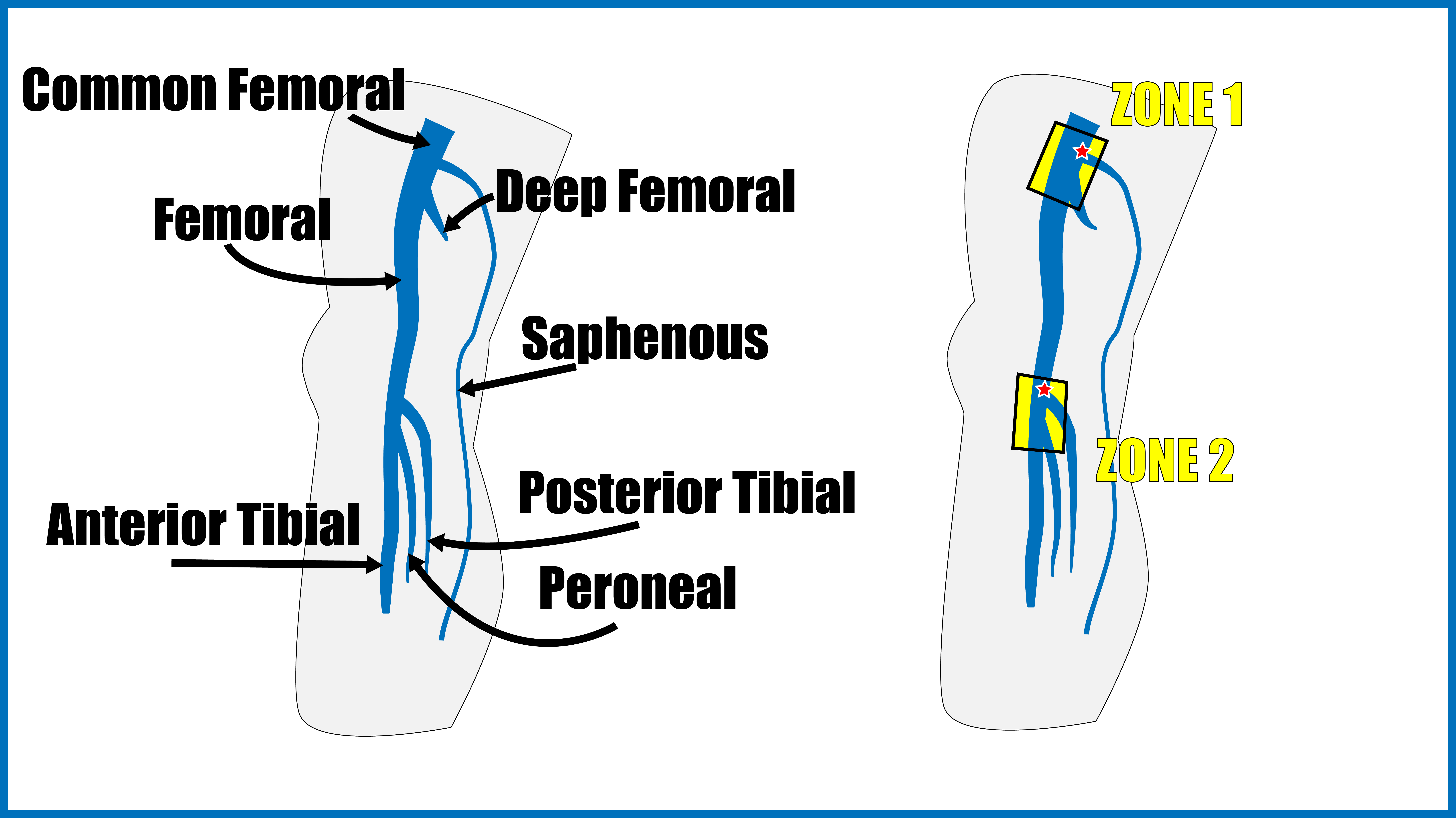

*The vein that was historically referred to as the “superficial femoral vein” is now commonly referred to as simply the “femoral vein“. The “common femoral vein” divides into the “deep femoral vein” and the “femoral vein” in the proximal thigh and the “femoral vein” courses distally down the thigh through the adductor canal at which point it is renamed the “popliteal vein“. The term “superficial” is omitted because it causes confusion as the “[superficial] femoral vein” is actually considered “deep vein”.

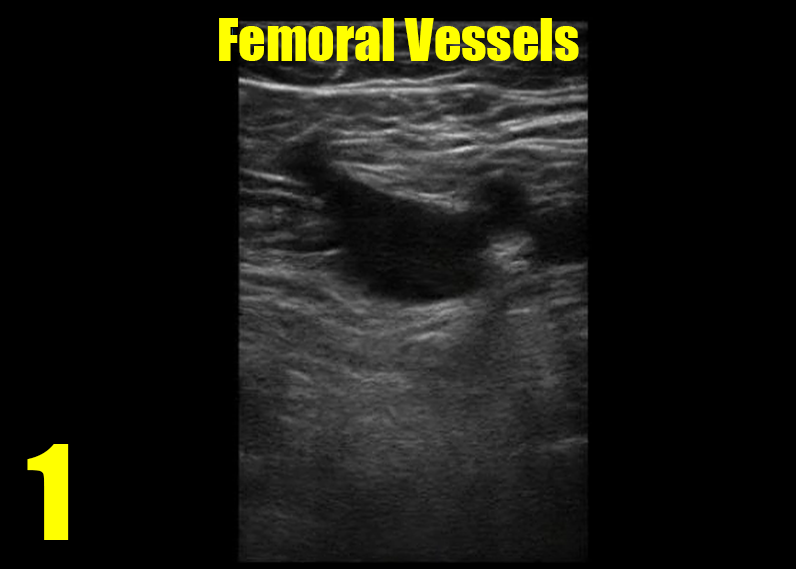

A mistake novices make is finding an impressive looking vein and mistakenly think that it is a deep vein – usually the common femoral vein or the femoral vein. Remember, a deep vein will always have an accompanying artery. They never run by themselves. If you are seeing an isolated vein, it’s not a “deep vein” and in this case is likely the saphenous vein. This happens in the popliteal fossa as well.

In the clip above, we actually catch a glimpse of the femoral vein in the right lower part of the image during the compression. Learners make this mistake frequently. Finding the SFJ is an orienting landmark you should use to begin your study. That’s home. Start from home every time. If you are finding veins without accompanying arteries, you probably need to increase the depth setting or at least scrutinize the deeper part of the image.

To master the other issues, an understanding of the anatomy is crucial. The image below shows the relationships among the vessels and highlights where the imaging zones are.

The saphenofemoral junction is the spot where flow is most turbid, and it is essential that your images include it. To truly meet the requirements of the exam, it is not good enough to get close. When I review learners’ studies that do not include this point, I worry that not only do they not appreciate the requirements of the study, but also they do not appreciate the anatomy and physiology of why clots develop where they do. When they omit the SFJ, it is almost always because they image too far distally. To see the SFJ, you have to get awkwardly high on the thigh and awkwardly medial, but it can be found on most (all?) patients. The saphenous should be seen coming off of the superiomedial aspect of the common femoral vein.

Notice that in the image below, the deep femoral is seen. It is a short vessel that is often elusive, but thankfully rarely contains an isolated DVT. I don’t find it on every study nor do I spend much time looking for it – but recognizing it and understanding why it is not an essential part of a limited DVT study demonstrates a high level of understanding of the procedure and its indications and limitations. I love it when a learner shows me the deep femoral vein. I hate it when they check the box indicating that they have seen it but none of their images include it – I know they haven’t mastered the material if they do that.

Behind the knee, the popliteal vein runs with the popliteal artery. It gives rise to three branches: the anterior tibial, peroneal, and the posterior tibial veins. They branch sequentially, and there are often many small, superficial branches visible on the screen at the same level or just below these branch points.

If you are looking at the vessels behind the knee and see more than one artery and one vein, you are below the branch point and you should move proximally as illustrated in the video below. For a zone approach, you should save a clip compressing above the trifurcation (only one artery and one vein in the image), then save another clip compressing below it (branches visible). I do not usually spend time compressing the calf veins, as they are not truly “deep veins” and I probably would not anti-coagulate clots isolated to calf veins anyway. The important point is that if you are seeing calf veins, you must be below the trifurcation.

One last example

Here is a study done by someone who is on the verge of mastery. These are very nice images and are very close to what we need – but not quite. They interpreted the study as negative; and, frankly, they are PROBABLY correct. However, there are some subtleties that got overlooked. Those subtleties might make the difference in this or any given patient.

This is case where the person performing the study did not quite get the required images, yet in the report they said they did. I’m not sure where the knowledge gap was – in fact there could be several in this case. Was it that they did not know what was required? Or did they know the requirements but not realize the images obtained were not of those required spots? Maybe they knew all of that, but just thought that this was good enough and no one would know the difference? I suppose it wouldn’t matter unless the patient came back next week with a pulmonary embolism. Would you want that for yourself or your family? If the point of care test is as good, sure, save me the time. But if you might miss something without realizing it and give me false assurance, I’d rather wait.

[I have to say here that “wait” may not always mean the same thing. It may mean wait for a tech study in the ED during that visit. Or it may mean wait for a D dimer to see if the test is necessary at all. It may mean a shot of enoxaparin and come back in the morning when the tech is available. It may also mean a very thorough discussion with the patient about the limitations of the bedside study and need for verification with a comprehensive study by a technologist. Your local protocols, practice patterns, and resource availability determine what “wait” means in a given patient at a given time.]

Wrap it up

At a minimum, to achieve any sort of sensitivity that would make it justifiable to do this study rather than taking the time to have a comprehensive one done, a point of care DVT ultrasound must include at least the following: either a video clip or still images before and after compression of the common femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction and the popliteal vein just above the trifurcation. To add sensitivity, compress several times through those regions rather than simply once and only once at those two points. To add even more sensitivity, compress the femoral vein every few centimeters down its length in the thigh. I think most of our residents could quote that to me. This post was to offer examples of times when images saved do not match stated findings and to show very specifically and clearly what the goal images are. It was long. But if you are making decisions about peoples lives based on these images, it is important.

Pertinent Articles

Not exactly a “referecencs” section, but here are some articles that support some of the claims I’ve made in this post

To support my stance that a two point study is an acceptable minimum (although I feel better about a zone approach and compressing the femoral vein between common femoral and the adductor canal), here is a meta-analysis showing similar sensitivities of two point vs three point compression point of care DVT studies in the ED:

To support my statement that most DVT occur at the two points in a two point study and that only a small percentage occurs between those two points without involving either of them, here is a study of 189 consecutive patients with DVT in which all crossed at least one of the two points:

If it sounds to good to be true that no DVT can occur without involving one of the two points, here is a study that showed that in 362 patients with DVT, 6.3% were found to not include one of those to points (i.e. were isolated to the femoral [5.5%] or deep femoral [0.8%] veins):

To support my claim that point of care DVT ultrasound can achieve a very high sensitivity, here is a study that reports 93%:

And here is a paper that summarizes several studies, some of which report a 100% sensitivity of ED providers and hospitalists that have adequate training in performing point of care DVT ultrasound:

Dr Steele: still writing bangers

Me: still using these as cheat sheets for attending life

LikeLike