Hypothetically, let’s say I was signing charts the other day and saw that on a particular patient a resident listed several things as admission diagnoses. One caught my eye.

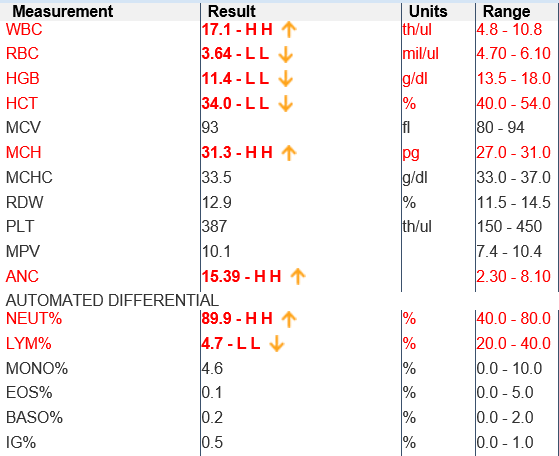

So, I looked back at the CBC to verify whether or not this patient actually had a left shift, because I suspected there was some confusion happening.

There certainly is a leukocytosis and a neutrophilia, but those are not what a “left shift” is. I’ve heard this term used incorrectly in this setting by both learners and experienced clinicians. Let’s take this opportunity to clear up a few things.

First, the term “left shift” comes from the handheld cell counters that laboratory technicians use to note how many of each type of cell is in the specimen they are examining.

These come in several configurations. Some have five keys, which allow separation into the five cell lineages of leukocytes we would see on peripheral smear. Others, like this one, have eight keys. The extra three keys allow for subdividing the neutrophils into their developmental stages.

Notice that on these cell counters, the immature forms of neutrophils are physically located to the left of the mature forms. This is the origin of the term “left shift.” It means there is a higher than expected percentage of immature neutrophils. It does not mean “elevated WBC count,” “elevated neutrophil count,” nor “neutrophil predominance.” Having a left shift means the marrow is producing neutrophils to meet a demand such that some are sent into circulation before they are fully mature.

Can one have an increased neutrophil count without a left shift? Yes. There are several places your body stashes mature neutrophils ready to use at a moments notice – specifically: in the marrow or adhered to various vascular tissues (the so-called “marginal pool”) (1). The marginal pool can be dumped into the circulation by many factors, one of which is epinephrine. So, if you get into a fist fight or run from a snarling German Shepherd, you will likely get an increase in your neutrophil count – but not a left shift. The stimulus does not have to be so dramatic, however. We’ve all seen patients with gastroenteritis who have been vomiting frequently with an elevated white blood cell count, but no identifiable bacterial infection nor left shift. They have ‘demarginated’ their stash of neutrophils in response to a physiologic stress – but do not necessarily have a “left shift.”

How do we see a left shift on the CBC? Some labs report ‘bands’ with the CBC. (The cell counter above uses the term “stab,” which is the same thing.) Bands are neutrophils one step away from maturity. Although debatable, there may be some utility to knowing the band count to help differentiate increased WBC production (‘bandemia’) from an elevated WBC due to use of the marginal pool.

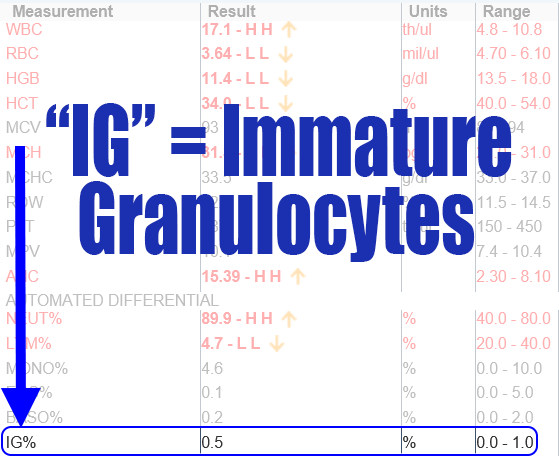

This brings me to my second learning point. Our lab does not report a band count. It does, however, report something called “IG%.” This IG is the “Immature Granulocyte” count.

Recall that eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils are all “granulocytes.” So, clearly the IG% is less specific to neutrophils than a true band count. However, my understanding is that the IG% can be measured with a machine as part of an automated differential; whereas band counts are more subtle and done by hand, which is laborious (2). The IG% represents promyelocytes, myelocytes, or metamyeloctyes; but not bands (2). The machine would likely include the bands as part of the total neutrophil count.

Is IG% a reasonable surrogate for a bandemia? I think so, but I can’t find a specific answer to that question. So, I suspect that a normal IG% means there is no left shift, but I don’t have reference for that particular fact. In other words, I suspect if you have an elevated percentage of bands, you would have an elevated percentage of promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes as well. I don’t think you’d have one without the other.

Back to the original patient: using the information available to us, I don’t think we can say that the patient in question had a “Left Shift” as the IG% is normal. Cutoffs used in research seem to be IG >3% and band>10%. Clinically, the significance of a neutrophilia without a bandemia may not be something you make a lot of decisions based on, but it’s good to know what the terms mean. Now we are all on the same page.

References:

- Hudnall, SD. (2012). Myeloid Cells. In W. Schmitt (Ed.) Hematology: A Pathophysiologic Approach (pp 49-58). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby.

- Farkas JD. The complete blood count to diagnose septic shock. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Feb;12(Suppl 1):S16-S21. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.12.63. PMID: 32148922; PMCID: PMC7024748.

Thank you!

LikeLike